|

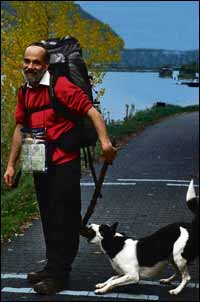

PROFILE Rabbi's epic walk with a blogging dog for company | |

YOU can take the Jews out of Germany, but you can't take Germany out of German Jews.

Although Rabbi Jonathan Wittenberg was born in Glasgow, the strong German roots on both sides of his family impelled him to make an intriguing journey by foot from Frankfurt to Finchley, where he is the rabbi of New North London Masorti Synagogue. His late maternal grandfather Rabbi Georg Salzberger was the rabbi until 1939 of Frankfurt's Westend-Synagogue, which was destroyed on Kristallnacht. But although the shul was totally gutted in the fire, its ner tamid (eternal light) continued to burn. After imprisonment in Dachau, Rabbi Salzberger and his family escaped to Britain courtesy of the British consulate in Frankfurt. Growing up in London, Rabbi Wittenberg, whose mother died when he was just five, was especially close to his grandparents who constantly regaled him with tales of German life and culture which still influenced them despite the horrors they had experienced in the prelude to the Holocaust. An extremely keen walker, the idea of walking from Frankfurt to Finchley came to Rabbi Wittenberg when he read his grandfather's memoirs on the 70th anniversary of Kristallnacht just before his Finchley congregation was rebuilding its synagogue. Armed with a battery-powered ner tamid and accompanied by his faithful dog, Mitzpah, who allegedly wrote his own blog on his journey, Rabbi Wittenberg walked from Frankfurt to the Hook of Holland, musing along the way on the history of German Jewry and connecting with righteous gentiles who supported Jews during the Holocaust. The bearing of the light from the land of the Holocaust to freedom in London became the subject of both the film, Carrying the Light, and the recently released book Walking With The Light - From Frankfurt to Finchley, published by Quartet Books, priced £20. Unlike the film, which has been screened at film festivals in London and Israel, the book allows Rabbi Wittenberg to describe the ambivalence which he and his family feel - and felt - to their fatherland of Germany. Germany for the Wittenbergs and Salzbergers was not just the site of the unspeakable horrors of the Holocaust, nor just the splendour of the German Enlightenment whose thinkers left their mark on his family's minds. It was also the history of German halachic giants who lived on the banks of the Rhine alongside which Rabbi Wittenberg and his dog strolled and dipped into historical and interfaith reminiscences. On his visit to Mainz, Rabbi Wittenberg recalled both Rabbenu Gershom, who ended polygamy in 1000, and tragic Rabbi Amnon, of Mainz, whose torture gave us the high holy days Unetaneh Tokkef prayer. Rabbi Wittenberg said: "Making the journey opened many doors for me. It made my sense of closeness to my family and its history deeper and greater. It strengthened an already strong bond." Rabbi Wittenberg's ancestors were Orthodox rabbis with his great grandfather Rabbi Moritz Salzberger serving on the Berlin Beth Din. The grandfather with whom Rabbi Wittenberg was so close in his early years, he describes in the book as "liberal". But Rabbi Wittenberg emphasised to me: "Liberal on the Continent meant much more like traditional Conservative than Liberal Judaism. "My grandfather never drove on Shabbat. He always kept kosher till he came to London and found himself a not-so-young refugee in a strange, huge city. He was far more traditional than what goes by the word 'liberal'." Yet Rabbi Salzberger, who knew from the age of three that he wanted to be a rabbi, was also deeply influenced by German culture to which he had an extremely inclusivist approach. I asked Rabbi Wittenberg, whose decision to become a rabbi came much more gradually and later, why he chose the Masorti Movement. First he told me how he came to be born in Bearsden, on the outskirts of Glasgow. His mother, the late Lore Salzberger, had been sent to study in Zurich in the 1930s as a safe haven from the Nazis. When the family finally fled Germany in 1939, Glasgow University was the only one in British to allow her to continue uninterrupted her course in German, French and Italian literature. After graduation in Glasgow, Lore took a doctorate at Oxford University and then joined the staff of Girton College, Cambridge. She made aliya to help found the German department of the Hebrew University. She met her husband, Adi Wittenberg, in Israel where his family had fled from Germany, managing to get on the 1937 quota. In then-Palestine, 16-year-old Adi had joined the British Army Royal Engineers. He then joined the Haganah. In the siege of Jerusalem he was the mechanical engineer responsible for the cooling of the blood bank. Finding it difficult thereafter to continue his higher education in the new Jewish state, Adi decided to come to Britain. He and his wife chose Glasgow because Lore still had friends there. Rabbi Wittenberg said: "They rented a room in Kirkintilloch for many years. It was absolutely not a Jewish area. Then they bought a bungalow in Bearsden. I was born in that house. "My first school years were there. Then unfortunately my mother died very young." He added: "My father studied for seven years at night school to get a degree in mechanical engineering. He would come home at midnight on the last train and walk the last two miles back through whatever weather. I had great admiration for that." After the untimely death of Lore, Adi and his two sons moved to London where he married his mother's youngest sister, Isca. In London Adi was one of the early supporters of Rabbi Dr Louis Jacobs who founded the Masorti Movement. Rabbi Wittenberg said: "My family were founder members of the New London Synagogue and my father became one of Rabbi Jacobs' greatest followers and friends. "He was on the synagogue council for many years, three of which he served as warden." An engineer by trade, Adi carried out repairs at Rabbi Jacobs' house as well as at his synagogue. After studying English at Cambridge, inheriting his mother's love of literature, and spending time in Israel teaching and studying, Rabbi Wittenberg studied to be a rabbi at Leo Baeck College and became a Masorti rabbi. He chose Masorti not just because of his family connections, but because it "embraced a Judaism that has been developmental, dynamic and creative". He said that, like Rabbi Jacobs, he feels that "one always has to take account not just of the divine, but also of the cultural and historical elements". But he added: "It is very important to have good relationships with different movements. "I understand that Judaism is well served by having a wide range of different kinds of synagogues. I am deeply committed to Masorti Judaism, but believe that it is important to co-operate with others."

|