|

PROFILE Pure luck saved Ida from Nazi round-up | |

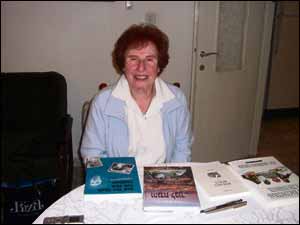

I HAVE rarely met a happier person than 83-year-old Dr Ida Akerman who hardly stopped laughing during the course of our two-hour interview in her Jerusalem home.

Yet psychoanalyst Dr Akerman, who looks 20 years younger, is a Holocaust survivor who was haunted for most of her life by painful flashbacks which prevented her from easily re-integrating into the Jewish community and living a normal life. The reason for our interview was the recent publication of the English edition of her book Et Tu Renconteras a tes Enfants, which took 20 years to write and which was published in French in 1995 and translated into Hebrew in 2002. And You Shall Tell Your Children - A Chronicle of Survival details Dr Akerman's long and hard - not only geographical but also emotional - journey from her parents' native Poland to Berlin, where she was born, and then on to Belgium and then France. It was from France that her parents Yehochua and Brucha Tieder were deported to Auschwitz. By a miraculous stroke of fate, 14-year-old Ida was absent on the day of the round-up from the small Provencal village in which she and her parents were incarcerated. After a ghastly premonitory nightmare, Ida's mother had sent her to get information about the rumoured round-up from a Jewish market trader who lived in Avignon. The trader had frequented the village of Le Sablet. where her family had been temporarily sheltered thanks to the intervention of a Rabbi Henri Schilli, who had been able to extricate them from a French concentration camp. As she was too young to require a travel pass, Ida had been sent by her parents who could not travel to try to find out information in order to plan how they could possibly hide in a village riddled with Nazi collaborators. But Mr Sokolowski of Avignon had no such information and he persuaded Ida to stay overnight till he could obtain some. With no luck the following day in August, 1942, Ida returned to find her home sealed and empty after the Auschwitz deportation. Still laughing, Ida told me: "I was alone in the world in my little summer dress with shoes of tissue - and not a cent. "Suddenly, I had no parents and no home with collaborators all around. I was crying, rooted to the spot in front of the door. No one asked if I wanted the toilet or a glass of water." So how, nearly 70 years later, can Dr Akerman now laugh about the horrific trauma she had undergone as a teenager? She admitted: "Underneath the laughter I am crying. I tell my story to Israeli children and every time I tell it I still cry." The secret of Dr Akerman's happiness lies in her gratitude. She says: "I am happy to be alive. When everything is taken from you, when it is not normal to have a house, you appreciate everything. "I am grateful for the privilege of living in Jerusalem and for being able to breathe the oxygen of Torah." She continued: "Today I can only get younger. After the war I was already 90 years old and perhaps a great deal more." It was indeed a difficult journey to reach her current happy destination. Ida came from a pious chassidic family. Her father's last message - thrown out of the train on the way to Auschwitz - counselled his children "not to rebel against God, to keep Shabbat and to be good to one another". But it was easier said than done. Ida was saved during World War Two by being looked after in a children's home run by secular French Jewish scouts where Ida and her sister and brother had to struggle to even have matzo on Pesach. But it was not just their physical conditions which distanced many survivors from their Jewish roots. Psychoanalyst Dr Akerman has discovered deeper psychological reasons why she and her generation found it difficult to reconnect with their Jewish heritage. The woman who now gives weekly Torah shiurim in Jerusalem writes: "It was 30 years before I was able to open a prayer book and pray. Until my return to Israel, I couldn't say a prayer aloud." She explained: "For many people it was only possible to live afterwards if one escaped from Judaism or its forms - anything that even remotely resembled certain images of one's previous life, anything that was perceived as dangerous, something doomed to death." This total dissociation from their past, which was a common fate of survivors, also affected their family life. She writes:"To return to the family mould, to conform to the model of one's parents, was no longer possible. It was death. I'm far from being the only person to react in this way. "Three generations have been affected in the same way - grandparents, parents and children." When 14-year-old Ida was left standing outside the sealed house in the village of Le Sablet, her first desire was to join her parents on their journey into the dreadful unknown. She said: "A child only wants to be with his or her parents." But Mr Sokolowski had persuaded her that she could help her parents escape if she did not go to them. Later, in the Moissac children's home, Ida discovered that the best way to build up a new life for herself was to gain an excellent education. Ida, her sister Sarah, brother Martin and fellow survivor her late husband Manfred Akerman all became top medical professionals. Having to suppress her feelings in order to achieve, she says: "I no longer had anything. No universe, no parents, nothing at all. "I didn't even have the right to memories. I didn't even have the right to mourning. I didn't have the right to be unhappy. Above all, one was not allowed to look unhappy." But her saving grace was, she said, that "I loved studying - I loved it immensely." So she threw herself night and day into her studies, deliberately choosing to study in the capital city of Paris where one could lose sight of all former connections. But professional and academic achievement came at a price. She writes: "Nobody can live if he cuts himself off from his roots and stifles his inner nature. "It's as though you took a tree and, in order to give it life and allow the sap to rise, you made a hole and filled its roots with cement." Ida's roots were her Jewish ones. She writes: "I couldn't live without this heritage. Shabbat and the holidays were paradise. They were life. On the other hand, every time I approached this world my sore point was touched and I couldn't bear it." Thus the religious paradox which plagued so many survivors. Trained as a psychoanalyst because she realised that without treating the traumas of the parents, she could not heal the sick children who came to her paediatric practice, Ida and her husband Manfred set about creating a Jewish environment in her district of Paris which was understanding of the sensitivities of survivors. Gradually, Jewish spirituality was re-injected into the dry bones of the survivors until in 1990 Ida and Manfred finally followed their children and her brother and realised their dream of settling in Israel, where post-Holocaust Judaism has been able to establish new, vibrant roots. And You Shall Tell Your Children - A Chronicle of Survival is published by Devora Publishing.

|